Each year, thousands of publications collectively deepen our understanding of the human brain and our ability to heal, influence, and alter it. These research efforts are essential to combat neurological and psychiatric diseases, whose prevalence increases as our life expectancy grows and our environment diverges from the one in which we evolved just a few thousand years ago. However, the benefits are not inherently linked to the knowledge produced by researchers. On the contrary, they entirely depend on how society as a whole decides to use it.

It is not the will of the researchers, but the vote of all citizens that will determine in which society this knowledge will find a function and the legitimate limits of its use. Personally, I am concerned about the use that will be made of my own work, both present and future. This is indeed why I am involved in the adventure of Hemisphère Gauche, as a way to escape a few hours a week from the austerity of the academic world to step into the chaotic but vital whirlwind of the real world.

The Development of “Biobanks”

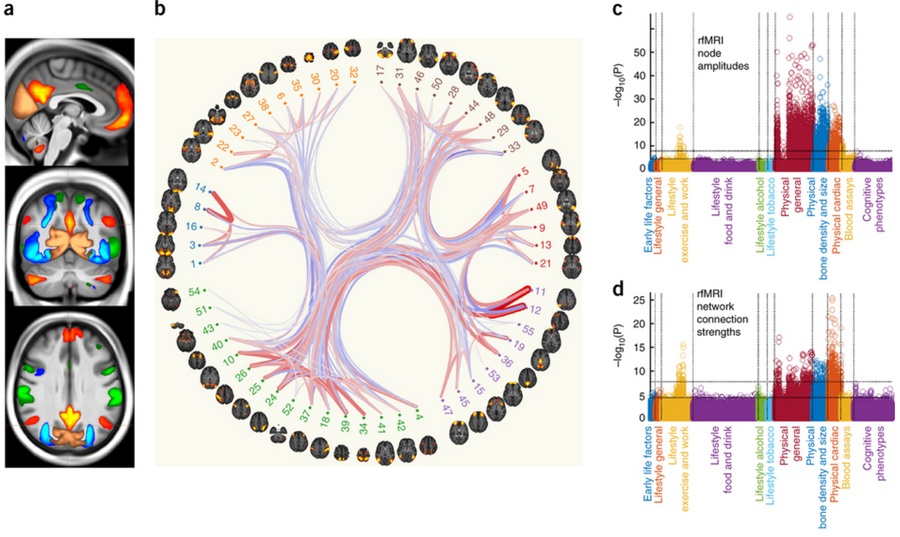

To take just one example, a study published on September 19 in the prestigious journal Nature Neuroscience describes the methods and initial results of the monumental “UK Biobank” project, which aims to collect a complete set of psychological, biological, and genetic data on 500,000 inhabitants of the United Kingdom aged between 40 and 70 by 2022. Its stated goal is the development of tools to predict the risks of developing certain neurodegenerative diseases on an individual scale, thereby facilitating the creation of new treatments to prevent their occurrence.

Unfortunately, in an economy as deregulated as ours, we can fear that this same knowledge may also allow insurance companies, banks, and employers to assess these same vulnerabilities before establishing a contract with individuals, resulting in more unequal access to healthcare, housing, and employment. The upcoming advent of such practices – for example, including a brain imaging exam in the hiring process – is not science fiction, as there are researchers (albeit a very small minority) who recommend their implementation within a few years.

Willem Verbeke from the University of Rotterdam, for instance, supports the idea that a battery of neurobiological exams could detect at-risk profiles in advance before hiring individuals for important positions:

“If someone wanted to become the director of a company, I would probably want a scan of their brain first to be sure they do not have psychopathic or autistic tendencies.” source (my translation)

In this specific case, good luck to Verbeke in detecting psychopathic tendencies by glancing at a candidate’s brain, because it will take neurosciences at least 20 years, if not more, to make such diagnostics. However, the problem is not so much practical as it is ethical. Other diseases, such as Parkinson’s, are much closer to being anticipated. And already, brain data can give a rough idea of an individual’s intelligence quotient, so much so that others imagine using it at the time of university admissions… What will we decide the day these technologies are truly available?

Imagining the Flip Side Without Undercutting Ourselves

Furthermore, the “screening” of populations for profit is not the only potential misuse of knowledge generated by neuroscience. There are others, which I will address in the future, among them the commodification of brain modification techniques, neuromarketing, and the fallacious use of scientific conclusions for political ends (we notably remember comments by Nicolas Sarkozy on pedophilia and suicidal tendencies).

It is obviously heart-breaking for researchers to communicate about these potential deviations, but it seems to me that a constructive dissemination of knowledge also involves warning against its less thrilling applications. Because we are best placed to imagine the benefits, as well as the risks, associated with the scientific advancements in which we participate.